TabCloud is a Chrome extension and Android app which allows you to save open Chrome windows and restore them on another computer or at a later date.

After being thoroughly disappointed by a talk from Mozilla labs about Weave (now called Sync) at last years FOSDEM (they appeared to have made very little progress in the last 3 years, and were not even planning to offer any kind of real-time synchronisation). I had decided to attempt to implement the open window/tab synchronisation feature for Google Chrome as an extension. At the time I planned to host the server for this using node.js and allow real-time synchronisation with changes automatically affecting any machines you currently had connected. After quickly writing a solution using websockets it became obvious this was a harder problem than I anticipated – synchronisation is hard, mainly when things go wrong, i.e. how do you deal with conflicts when multiple machines have flakey connections, also the Chrome extension API makes it very difficult to distinguish the difference between closing all a windows tabs, and closing the window – so the project in that form was abandoned until I could find more time for it.

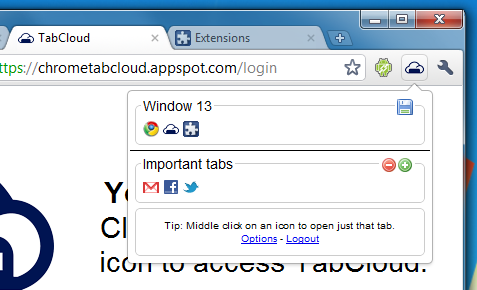

Fast-forward to the summer and I am working at IBM as a technical intern for Extreme Blue, I have a work laptop, home computer and my personal laptop, I am still using Chrome as my main browser and I would really like a way of sharing my browser sessions between my machines. I had recently created LinkPush (something I intend to blog about shortly), which made me think of using Google App Engine to host a simplified session sharing plugin for Chrome using Google Accounts as a means of secure identification. The result – TabCloud – is an extension which allows you to save an open window as a group of tabs, which can be restored on any other computer (or the same computer at a later date) via the extension interface. It also offers some other features such as naming windows, and re-arranging tabs between open windows and saved sessions by dragging and dropping the tab icons. I also released a very simple Android app which allows you to view your saved tabs as a list from your phone and open any individual link.

The project isn’t really anything like my original plans, however I find it extremely useful, hopefully at some point I will find the time to make a truely real-time session synchronisation app (unless Google beat me to it). Firefox 4 beta comes with the current Mozilla Sync (also available as an extension for older Firefoxes), which periodically saves all your open tabs (as well as other data) to their server, which allows you to view open tabs on one machine from another (or mobile device), however (despite this being more what I originally aimed for) this seems a lot less useful in practice than the simpler functionality I have implemented with TabCloud.

If you are interested the whole project is open source and available on GitHub.

I’ve wanted to experiment with some of the various graphics libraries in JavaScript for a while now, and deciding to attempt the ambitious task of a 2D clone of the recently popular game, MineCraft, seemed a worthy reason to play around with some of them.

After deciding (perhaps wrongly) that Raphaël would be a good library to do this in (or at least one I would like to try out). A quick weekend of implementing and reimplementing various ways of rendering scrolling around a vast 2D block world (in the end using a massive SVG element that is scrolled with blocks being added or removed as they come into and leave the visible area). The results are (not quite 2D MineCraft yet I know) a massive editable grid of “pixels” which are actually rounded rectangles of various colours.

As I wasn’t going to complete 2D MineCraft in a weekend I decided to add in websocket support using Socket.IO and make it a multi-user editable canvas that persists between sessions. Its quite fun to play with and there is a small demo below (works best in Chrome, Safari or IE9, should work slowly in Firefox), for a full page version click here, the last part of the URL defines the “channel” you are in if you wish to create a private page to share with friends.

If you are interested in the source just view the source of that page, I’ll be uploading the server and client to github shortly (once I’ve tided up some of the code a bit). If I have some time in the future I hope to take this further and make some kind of user editable platformer type game in the general theme of MineCraft. I would also like to try implementing this using the HTML5 canvas element (especially with the recent hardware rendering developments on Chrome and IE9).

So, after several months of neglect I have finally decided to force myself to update my blog. This is the first of what will hopefully be several posts detailed the various projects I have been working on over the past few months. This is the smallest and potentially least useful of these projects, but something I recently made (and therefore easiest for me to write about) and hopefully mildly interesting.

In the 2nd year of my computer science degree a module called “Artificial Intelligence” briefly touched on the idea of Genetic Algorithms. After discussion with a housemate as to how these could be used in a 3rd year project I decided to look into making a simple example of such an algorithm to run using JavaScript in the browser.

After a quick Google the best example I could find (that would be visual enough to be interesting to see and simple enough to write in JavaScript quickly) was to generate the string “Hello, World!”. Starting with randomly generated strings and genetically evolving them based on a fitness function of how close they were to the string I wanted. A little bit more detail on how that is achieved shortly, but first the result is shown below (click on “Hello, World!” to replay the demo) a more detailed output can be seen here.

So, what is this actually doing? Viewing the detailed output you can see all of the strings generated, how they were combined (the algorithmic equivalent of reproduction) and the mutatations after they reproduced. To start 20 random strings are generated, then the top 2 strings (measured by number of letters that are correct, and then closeness of incorrect letters) are taken. It is worth noting this is perhaps not the best way for a genetic algorithm to work, and strictly all of the strings should have a chance of “reproducing” based on their fitness score, but this works well enough for a simple example. Once the top 2 are taken, they are split at a random point 20 times and combined (shown by the red and green colouring on the detailed output), these resulting strings then have a 75% chance of one of their characters randomly changing (shown with a yellow highlight on the detailed output) and we have 20 (potentially) completely new strings. The scoring process then repeats and more strings are created until we reach the goal string.

The result is we very quickly get a string very close to what we want, which eventually mutates to become exactly what we want, with a nice visual demonstration of what is happening, and hopefully a better understanding of how genetic algorithms work.