Posts tagged ‘android’

![]() PassHash is a Chrome extension, Android app and website which allows you to generate strong, unique passwords using a master password and key based on the site you wish to use the password on.

PassHash is a Chrome extension, Android app and website which allows you to generate strong, unique passwords using a master password and key based on the site you wish to use the password on.

Having secure passwords for every site you visit is difficult, in reality many people (including me) use the same password for more than one place. This is bad as it increases the potential problem if your password is compromised, for example, if you share your email account’s password with another website, who then (accidentally or intentionally) give away your password, your email is no longer secure. There are a number of methods of reducing these problems and PassHash uses a technique which generates new passwords based on one secure password which you never share directly with anyone. It is worth noting that PassHash is far from unique, and there are many similar tools, as well as alternatives like LastPass, however, none of the alternatives met my requirements, as I will describe below.

PassHash works by taking your master password (which should be a password which is complicated, long and only known by you), and combines it with a memorable key for each website you want to use it on (using the domain name is the default, i.e. amazon.com or ebay.co.uk). This combination is then transformed in a way that cannot be easily reversed (using SHA-1), and modified to start with a lower case letter, followed by a number, followed by an upper case letter, and finally 9 more characters which can be lowercase, uppercase, or numeric. You can then use this password for the website with the key you gave, and know that you will be able to generate it again in the future, but no one else will.

So, why is PassHash better than any of the available alternatives?

- PassHash has no settings (unlike most of the alternatives), this might seem to be a bad thing, but settings are something else to remember, and something that could be wrong by default. PassHash attempts to have sensible defaults, and generate passwords accepted on as many websites as possible. Passwords generated are 12 characters long, and always include at least one of each of lowercase, uppercase and numeric characters. Longer passwords may not be allowed on all websites, and are harder to type if you need to manually enter them. Symbols are often not allowed in passwords and are also hard to type, especially if being input on a phone or other mobile device.

- PassHash is accessible from anywhere, there is a Chrome extension for use on your own computer, as well as a website you can use anywhere. There is also an Android app which allows you to generate passwords without entering your master password on a computer you may not trust. As nothing is stored PassHash also works even when you have no internet connection.

- The PassHash algorithm is simple and the source code is available, there is no need to trust that it generates passwords in a sensible way, you can check for yourself. As well as this, if I were to withdraw the Chrome extension anyone could release software to generate the same passwords.

- PassHash doesn’t store any of your passwords – including your master password – anywhere, locally or remotely. Services such as LastPass are always at risk of attack and by using them you are trusting the LastPass developers have not made any mistakes which could result in your passwords not being properly encrypted.

- PassHash is completely free, and always will be, with no potential for me to change this, as the source code is publicly available and no part of PassHash is provided as a service.

- The PassHash chrome extension can automatically enter generated passwords into text boxes on websites, this avoids both showing the password on the screen and storing the password in the clipboard at any point.

While this all sounds great, PassHash does have a couple of downsides.

- All of your passwords being based on one master passwords requires you to keep that password completely secret, if you compromise that password, none of your passwords are safe. Unlike services such as LastPass if you compromise your master password you will need to change your password on every site you used PassHash to generate passwords for. This means you must be particularly careful when entering your master password on any computer or device you do not fully trust.

- Remembering passwords generated with PassHash is not really an option, which is not necessarily an issue as long as you have ways of accessing your passwords while not at your computer, which is why the website and Android app exist

Website: http://passhash.connorhd.co.uk/

Source code: GitHub

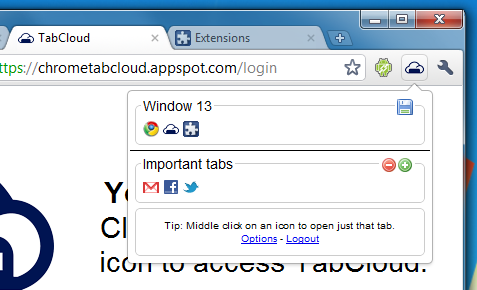

TabCloud is a Chrome extension and Android app which allows you to save open Chrome windows and restore them on another computer or at a later date.

After being thoroughly disappointed by a talk from Mozilla labs about Weave (now called Sync) at last years FOSDEM (they appeared to have made very little progress in the last 3 years, and were not even planning to offer any kind of real-time synchronisation). I had decided to attempt to implement the open window/tab synchronisation feature for Google Chrome as an extension. At the time I planned to host the server for this using node.js and allow real-time synchronisation with changes automatically affecting any machines you currently had connected. After quickly writing a solution using websockets it became obvious this was a harder problem than I anticipated – synchronisation is hard, mainly when things go wrong, i.e. how do you deal with conflicts when multiple machines have flakey connections, also the Chrome extension API makes it very difficult to distinguish the difference between closing all a windows tabs, and closing the window – so the project in that form was abandoned until I could find more time for it.

Fast-forward to the summer and I am working at IBM as a technical intern for Extreme Blue, I have a work laptop, home computer and my personal laptop, I am still using Chrome as my main browser and I would really like a way of sharing my browser sessions between my machines. I had recently created LinkPush (something I intend to blog about shortly), which made me think of using Google App Engine to host a simplified session sharing plugin for Chrome using Google Accounts as a means of secure identification. The result – TabCloud – is an extension which allows you to save an open window as a group of tabs, which can be restored on any other computer (or the same computer at a later date) via the extension interface. It also offers some other features such as naming windows, and re-arranging tabs between open windows and saved sessions by dragging and dropping the tab icons. I also released a very simple Android app which allows you to view your saved tabs as a list from your phone and open any individual link.

The project isn’t really anything like my original plans, however I find it extremely useful, hopefully at some point I will find the time to make a truely real-time session synchronisation app (unless Google beat me to it). Firefox 4 beta comes with the current Mozilla Sync (also available as an extension for older Firefoxes), which periodically saves all your open tabs (as well as other data) to their server, which allows you to view open tabs on one machine from another (or mobile device), however (despite this being more what I originally aimed for) this seems a lot less useful in practice than the simpler functionality I have implemented with TabCloud.

If you are interested the whole project is open source and available on GitHub.

I have again become interested in what you can do with Android applications. After some discussion with a housemate (who actually owns an Android, unlike me) about augmented reality applications and how they could be easily done (to some degree) if you could reasonably accurately track a phones location in a building (something that is hard to do with GPS). I wanted to see if the phones accelerometer could be used (at least for short distances) to work out how a phone had moved since entering a building. Rather than attempt to make an augmented reality app, I decided to go for a slightly easier project of making a tape measure, i.e. an app that could measure distance by moving the phone. Before anyone thinks this will actually be useful I should point out that this was a rather complete failure and the resulting app is fairly useless. However, the code may be useful to anyone looking at writing an Android app that uses any of the internal sensors, it would also be interesting to see if any other phones (I only tested the app on a G1) are any more successful.

So straight to the code, after (briefly) reading the Android documentation it seemed there was very little info about using the sensors, so I turned to Google, this article looked like what I wanted and linked to this code which is the basis of my app. So I updated the code to use the non-deprecated API, changing its functionality slightly and ended up with:

package uk.co.connorhd.android.tapemeasure; import android.app.Activity; import android.os.Bundle; import android.hardware.Sensor; import android.hardware.SensorEvent; import android.hardware.SensorEventListener; import android.hardware.SensorManager; import android.view.View; import android.view.View.OnClickListener; import android.widget.Button; import android.widget.TextView; public class TapeMeasure extends Activity implements SensorEventListener, OnClickListener { private SensorManager sensorMgr; private Sensor sensorAccel; private TextView accuracyLabel; private TextView xLabel, yLabel, zLabel; private Button calibrateButton; private float moved = 0; private float speed = 0; private float accel = 0; private float accelDiff = 0; private float[] a; private long lastUpdate = 0; private float curAccel = 0; private int accelUpdates = 0; @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); setContentView(R.layout.main); accuracyLabel = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.accuracy_label); xLabel = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.x_label); yLabel = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.y_label); zLabel = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.z_label); calibrateButton = (Button) findViewById(R.id.calibrate_button); calibrateButton.setOnClickListener(this); } @Override protected void onPause() { super.onPause(); sensorMgr.unregisterListener(this, sensorAccel); sensorMgr = null; } @Override protected void onResume() { super.onResume(); sensorMgr = (SensorManager) getSystemService(SENSOR_SERVICE); sensorAccel = sensorMgr.getSensorList(Sensor.TYPE_ACCELEROMETER).get(0); boolean accelSupported = sensorMgr.registerListener(this, sensorAccel, SensorManager.SENSOR_DELAY_FASTEST); if (!accelSupported) { // on accelerometer on this device sensorMgr.unregisterListener(this, sensorAccel); accuracyLabel.setText(R.string.no_accelerometer); } } public void onClick(View v) { if (v == calibrateButton) { // Clicked button moved = 0; speed = 0; accelDiff = accel+accelDiff; accel = 0; } } public void onAccuracyChanged(Sensor sensor, int accuracy) { // this method is called very rarely, so we don't have to // limit our updates as we do in onSensorChanged(...) if (sensor.getType() == Sensor.TYPE_ACCELEROMETER) { switch (accuracy) { case SensorManager.SENSOR_STATUS_UNRELIABLE: accuracyLabel.setText(R.string.accuracy_unreliable); break; case SensorManager.SENSOR_STATUS_ACCURACY_LOW: accuracyLabel.setText(R.string.accuracy_low); break; case SensorManager.SENSOR_STATUS_ACCURACY_MEDIUM: accuracyLabel.setText(R.string.accuracy_medium); break; case SensorManager.SENSOR_STATUS_ACCURACY_HIGH: accuracyLabel.setText(R.string.accuracy_high); break; } } } public void onSensorChanged(SensorEvent event) { int sensorType = event.sensor.getType(); if (sensorType == Sensor.TYPE_ACCELEROMETER) { a = event.values; accel = (float) (Math.sqrt((a[0]*a[0]+a[1]*a[1]+a[2]*a[2]))-SensorManager.GRAVITY_EARTH)-accelDiff; curAccel += accel; accelUpdates++; long curTime = event.timestamp - lastUpdate; if (curTime > 1000000000) { curAccel = curAccel/accelUpdates; speed += curAccel*curTime*10e-10; moved += speed*curTime*10e-10; lastUpdate = event.timestamp; xLabel.setText(String.format("Moved: %+2.20f", moved)); yLabel.setText(String.format("Speed: %+2.20f", speed)); zLabel.setText(String.format("Accel: %+2.20f Time: %+2.3f", curAccel, curTime*10e-10)); curAccel = 0; accelUpdates = 0; } } } }

This calculates the current acceleration of the phone, subtracts gravity (which is added to the raw data), then derives the speed and distance travelled. The calibrate button resets the speed and distance, and assumes the phone is not moving, generating a bias to add to the acceleration in the case of the phones accelerometer being badly calibrated. If you want to try the app it can be downloaded and installed from here. I suggest launching the app, placing the phone on a stable surface and pressing calibrate, if you get any interesting results let me know.

Despite the phone reporting the accelerometer accuracy as “high” (with no description of what high means) and returning values in excess of 10 significant figures, the acceleration data with the phone sat on a table varied in the range of about 0.5m/s^2 (although this did appear to change depending on the room I was in). This resulted in a massively wrong distance value very quickly increasing to several metres without moving the phone, making any kind of testing almost impossible. It seems the current purpose of accelerometers is to work out if some violent action (such as shaking) has happened to the phone, and not anything much more interesting. All in all a bit of a waste of time, but maybe future phones will have better sensors, and hopefully someone will find the code snippet above useful.